Early Greek Immigration to Saskatoon

Saskatoon’s History Through the Lives and Experiences of its Greek Community

The first Greek to arrive in Saskatoon was Kostas Valaris in 1901, just short of twenty years after the first settlers established the townsite. Little is known about Valaris and it appears he did not stay long encough to make his mark on Saskatoon’s Greek history. Nevertheless, many more Greeks subsequetly discovered Saskatoon as a good place to work, establish homes, and eventually, to raise their families.

The Greeks who came to Saskatoon priot to the 1920s are known as the “pioneers” of the Greek community. They laid the foundation for this community’s presence in Saskatoon.

When they arrived in Saskatoon, the Greek pioneers consisted mostly of young single men who were in their late teens and early twenties. They came from rural areas in Greece and were sent by their families to North America to work. They maintained strong ties to Greece through a sense of patriotism and a responsibility towards financially supporting their families there.

Padrone System

The early Greek immigrants often came to North America through United States ports. Many arrived through the padrone system. To secure trans-Atlantic passage and employment upon arrival in North America, labour brokers (padrones) arranged contracts involving the immigrants, steamship companies, and employers.

Padrones were often recent immigrants or first-generation Greek-Americans who had ties to rural villages in Greece where families were told stories about the potential fortunes their sons and brothers could make if they signed on. Many of these stories were exaggerated and misleading. The potential employment involved unskilled and manual work, at low wages, and under exploitive conditions.

The padrones facilitated the selection of the immigrants, financed the trans-Atlantic travel (usually in steerage class), took the risk that entry would be granted by U.S. authorities, provided the connection to employers, and arranged for accommodations which might be at the workplace or in crowded apartment buildings. Fees were charged by the padrones and immigrants reimbursed all costs through their future wages. Often, immigrants worked for many months with most, if not all, of their pay going to repay the padrones.

World War I curtailed the flow of immigrants to North America and made the padrone system inoperable. By 1930, the system was no longer functioning.

Patras, Greece, in 1910: Greek emigrants board small boats which will take them to a steamship bound

for North America.

United States Library of Congress and U.S.A. Greek Immigration

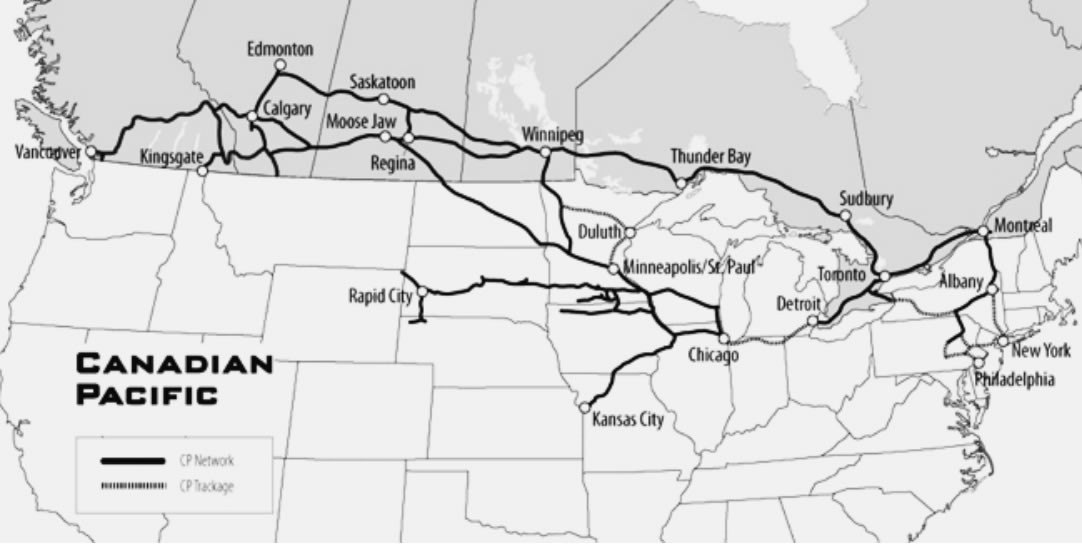

. Soo Railway Line

After the newcomers had paid the financial costs associated with their immigration, they were free to seek out better employment opportunities. Because they were mostly single men who had no family attachments in North America, they were very mobile. All their belongings could be carried in suitcases.

They sought out communities where others from their hometown or region in Greece were living. Chicago, for example, had a large Greek immigrant community from the Peloponnesus area of Greece. Many Greeks established roots in North America through businesses in Chicago; naturalization as U.S. citizens allowed them to begin sponsoring other relatives and friends to emigrate.

Others chose to move elsewhere in North America where people from their region in Greece had settled and which held promise for employment. Western Canada met these conditions and the rail connections facilitated moving to Canada.

The Soo Line provided a direct route to Moose Jaw, through Minneapolis and the international border at Portal North Dakota/Saskatchewan. Once in Moose Jaw, rail links were available to other communities in western Canada, including Saskatoon.

Very few of the Greek pioneers came to Saskatchewan to become farmers, even though they were largely the children of farm families in Greece. They were not familiar with the grain farm practices required to succeed here; their experience was with crops like olives, various types of fruits. potatoes, and raisins. In Greece, the farming operations were not mechanized and they relied on farm animals, rather than machinery, during harvest.

For most, their first jobs involved menial work, like dishwashing, in the kitchens of confectioneries, tea rooms, and restaurants. These jobs allowed them to begin working immediately upon arrival and before they has sufficient knowledge of the English language to interract with customers.

A war between Greece and Turkey forced many Greeks to leave Asia Minor after 1922. Many settled in mainland Greece; others came as refugees to western Canada, including Saskatoon.

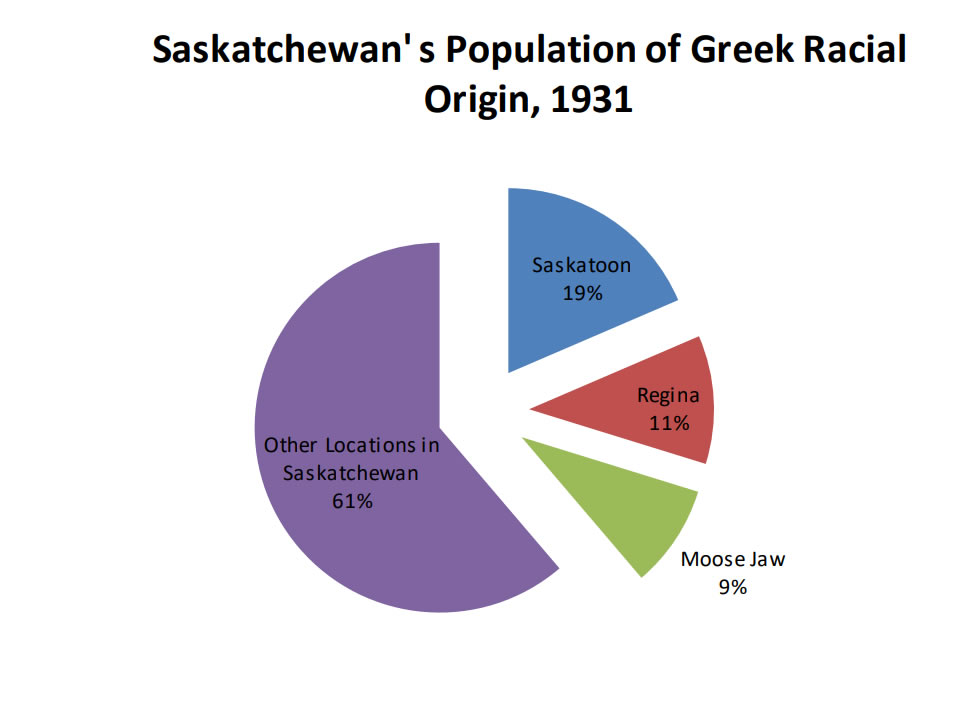

In 1931, 534 people in Saskatchewan were of Greek racial origin. Almost all lived in urban areas. The largest concentration was in Saskatoon, with 99 people. Records show that only three Greeks chose to farm in Saskatchewan – Gus Christakos and Bill Camche near Prince Albert and William Angelopoulous near Biggar.

Hopes of returning to Greece became impossible due to the 1930s depression, business commitments, and the establishment of families through marriage and the birth of children in Canada. Greeks in Saskatoon concluded that Canada would be their new permanent home and they sought naturalization (citizenship). Some Greek families in Saskatoon left for the west coast. About 25 families remained and developed a strong and closely-knit community of Greeks here.

Many Greek male immigrants had postponed their marriages until they were financially secure by owning businesses. Others remained as bachelors. Very few women immigrated to Canada in the early years, unless they came to join a father and reunite a family unit or were betrothed through a pre–arranged engagement through family connections in Greece. Many male immigrants married local non-Greek women. Others traveled to cities in Canada and the United States with larger Greek populations in search of a bride.

Following World War II, families in Saskatoon sponsored the immigration of young people and families from Greece. Many were family members; others were friends of the newly arrived immigrants.

Arriving From Greece

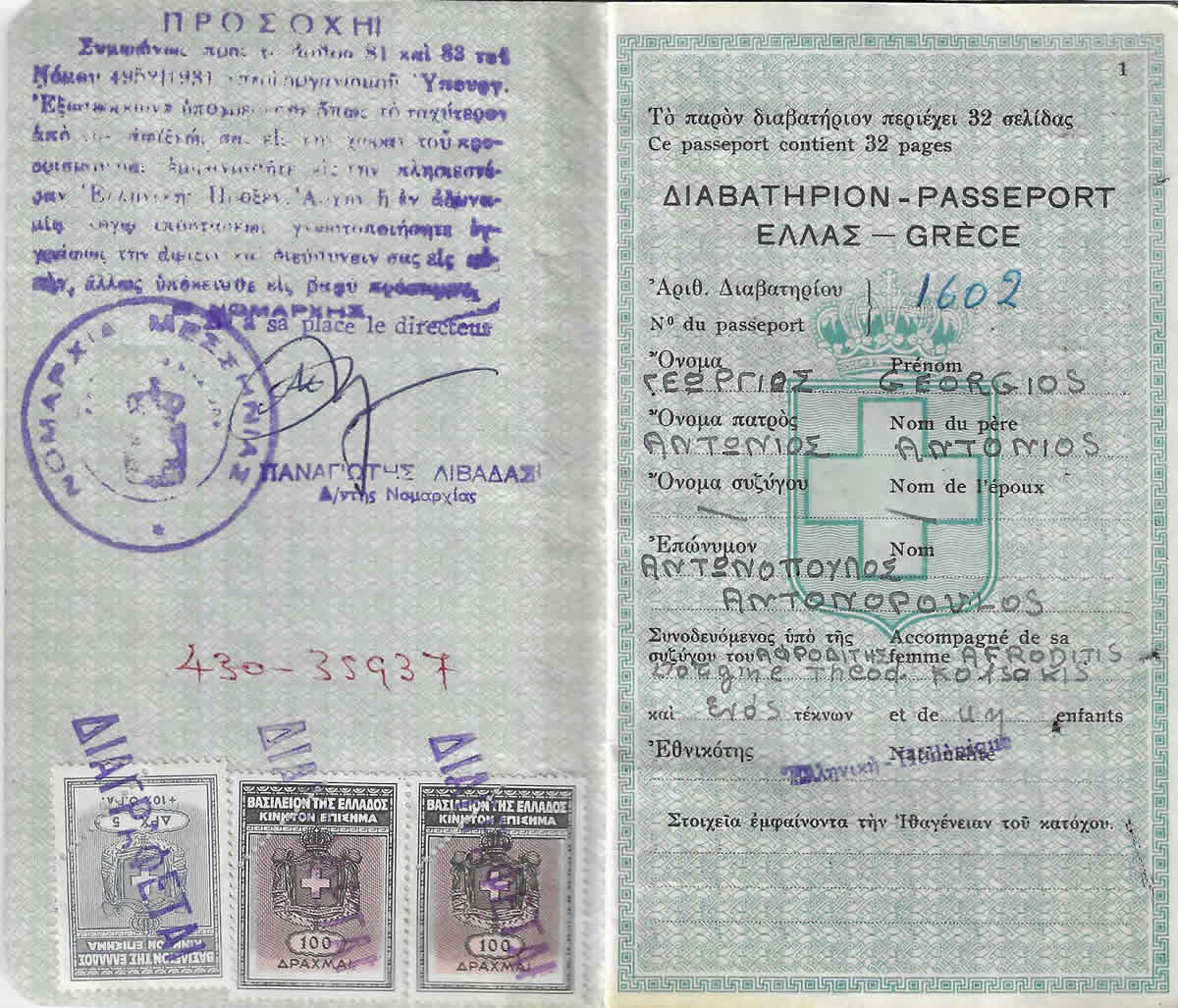

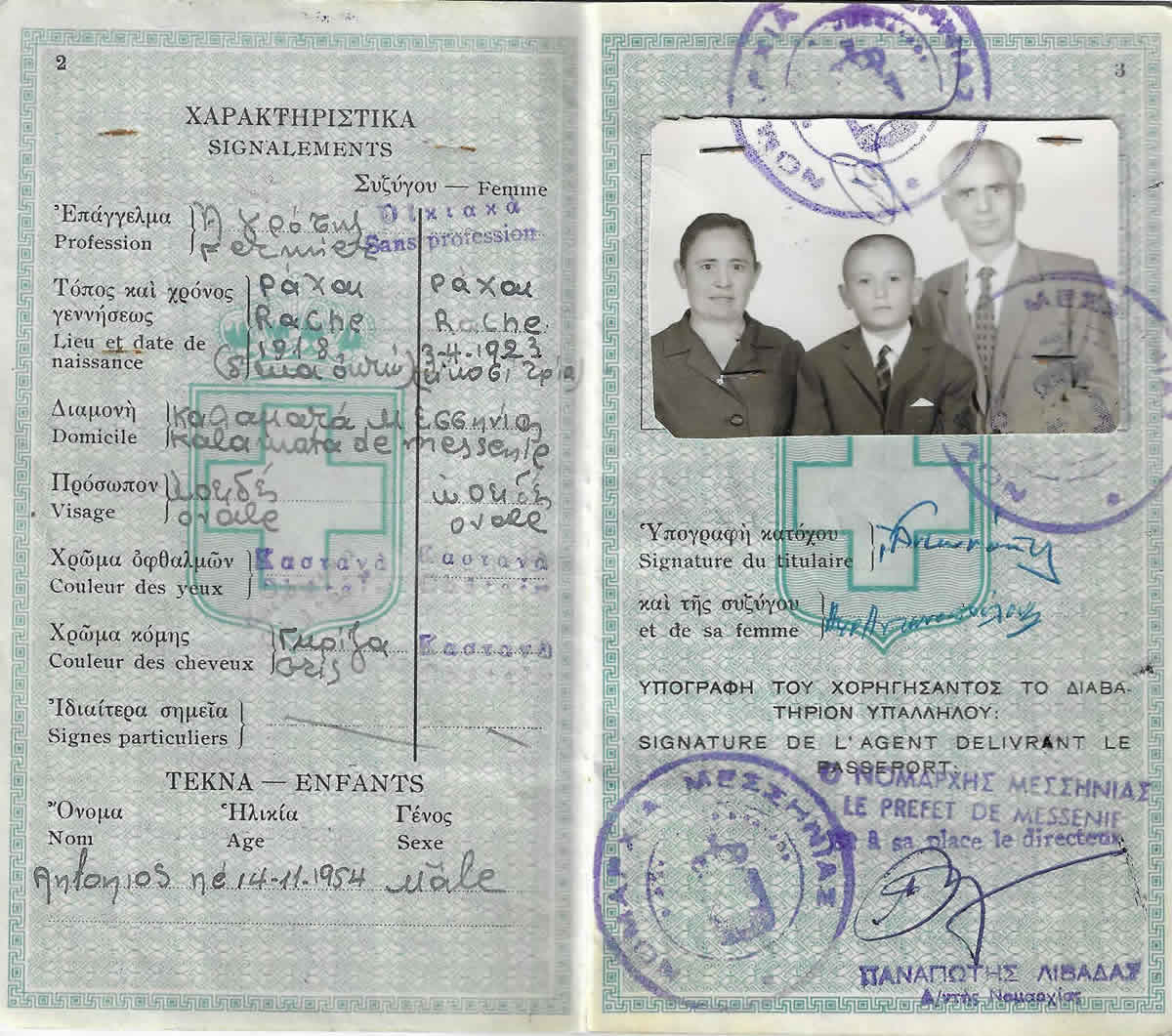

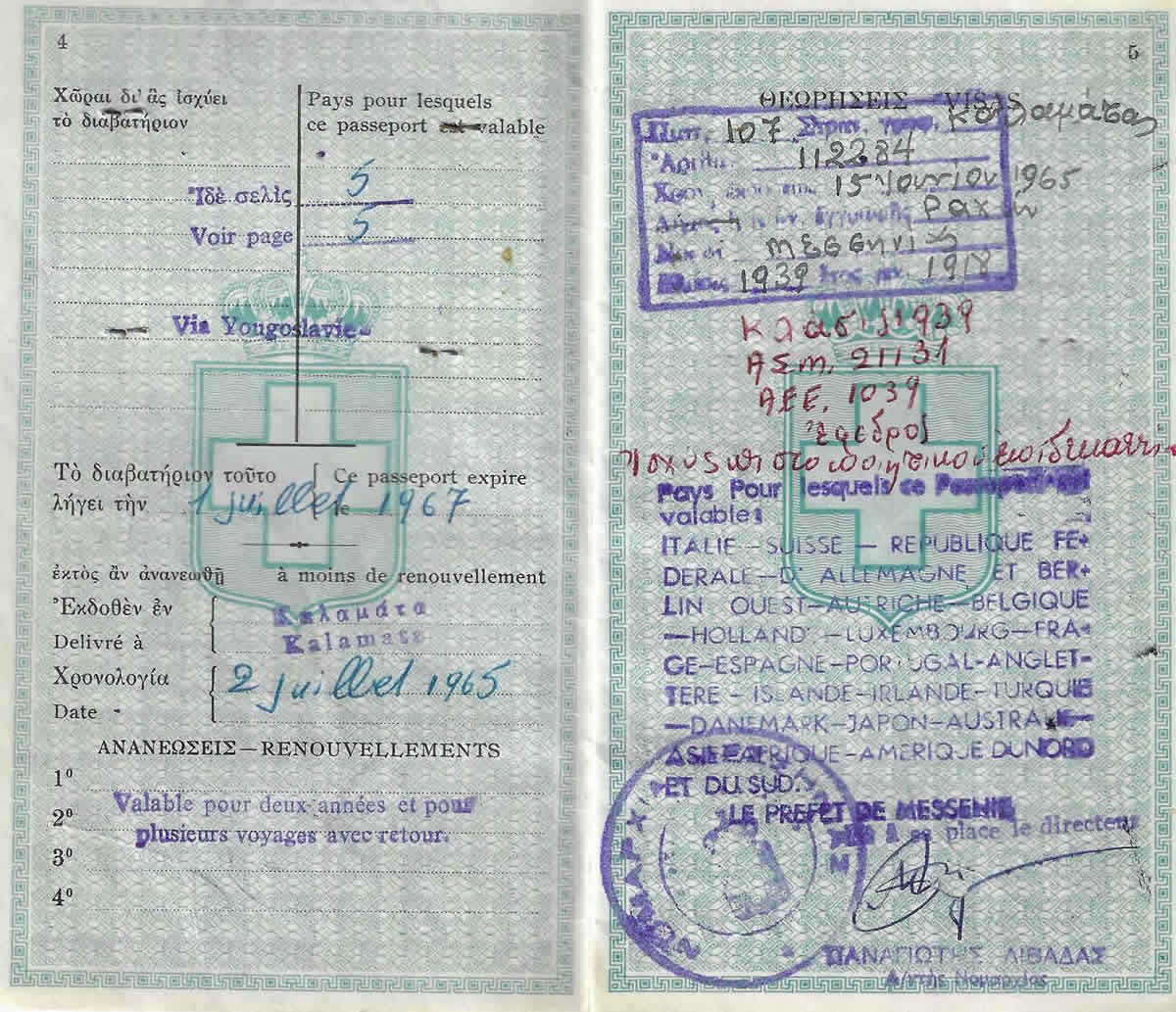

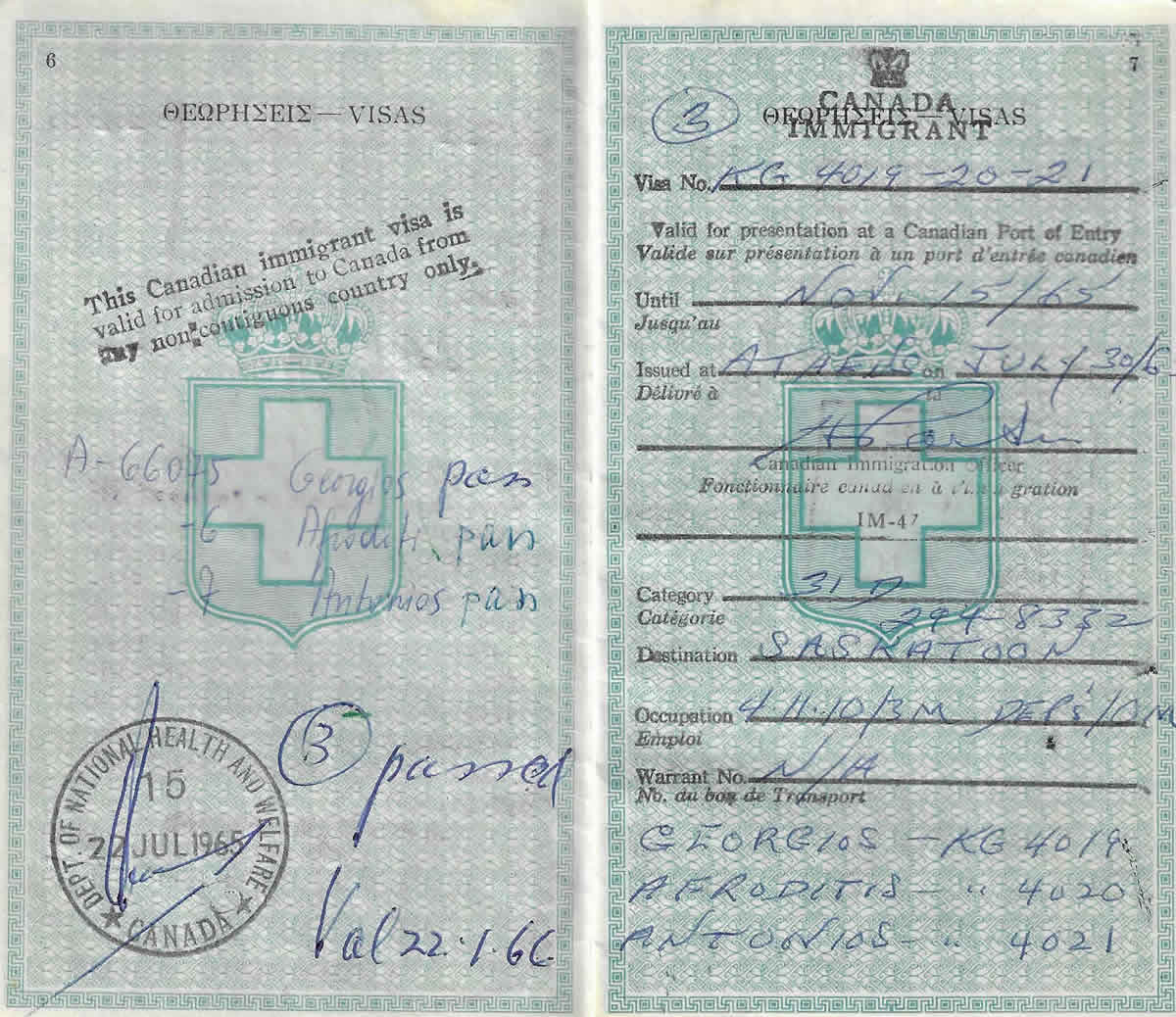

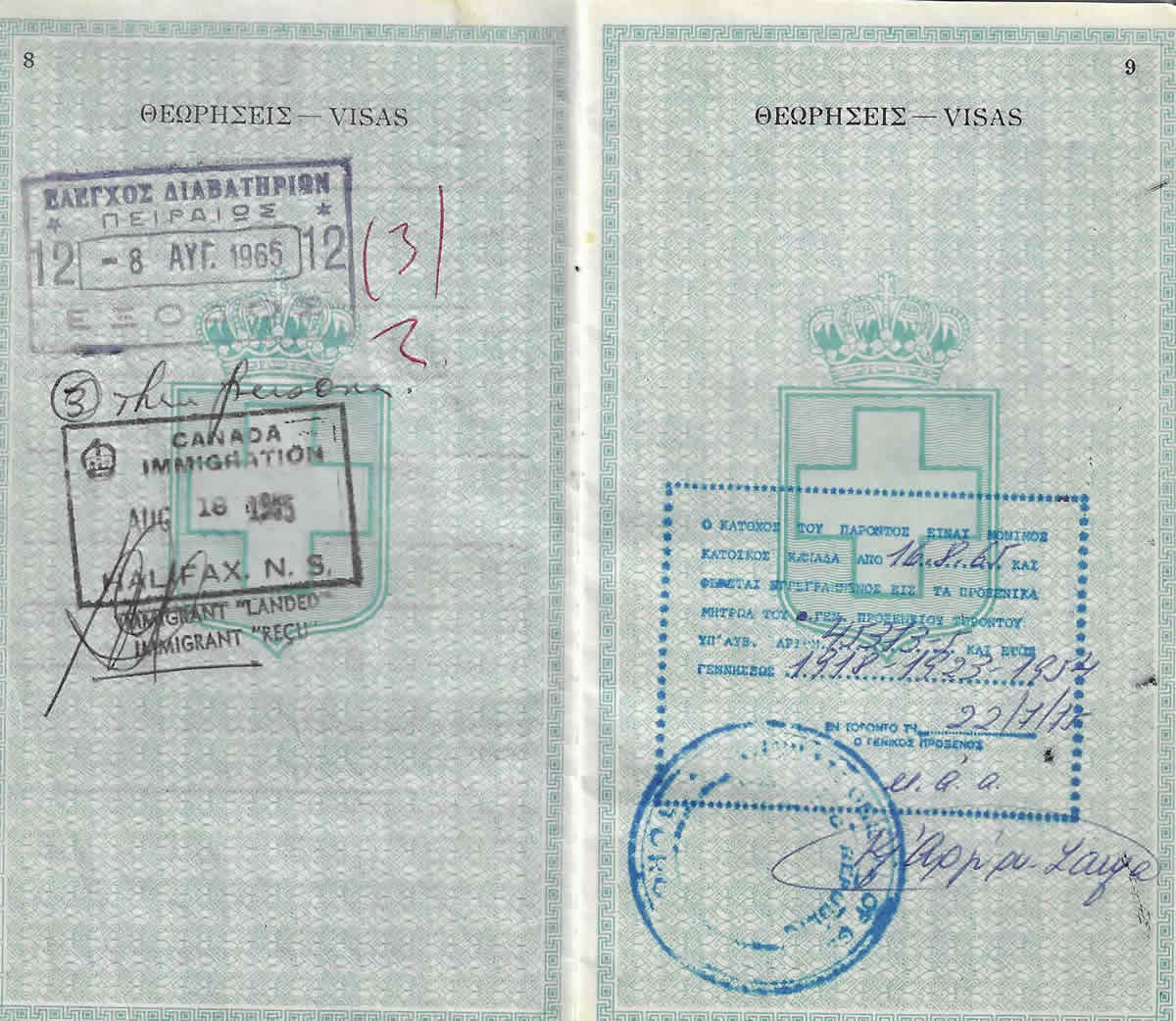

Below is an actual Greek passport of the Antonopoulos family who immigrated to Canada from Greece. They arrived in Halifax aboard the ship named Olympia on August 18, 1965. They continued by train to Saskatoon arriving August 21, 1965. Their adventure was similar to many Greek families who immigrated to Canada during those years.